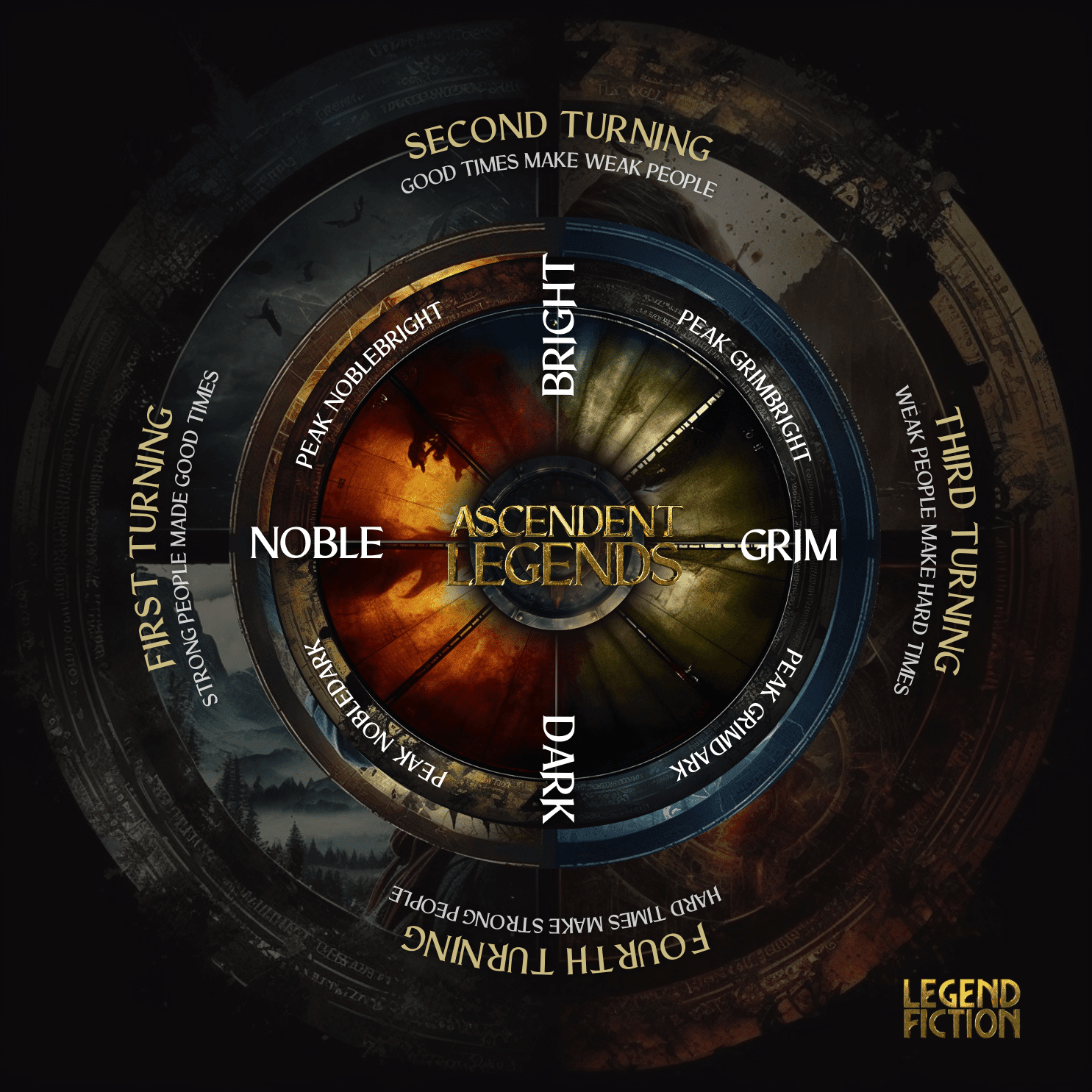

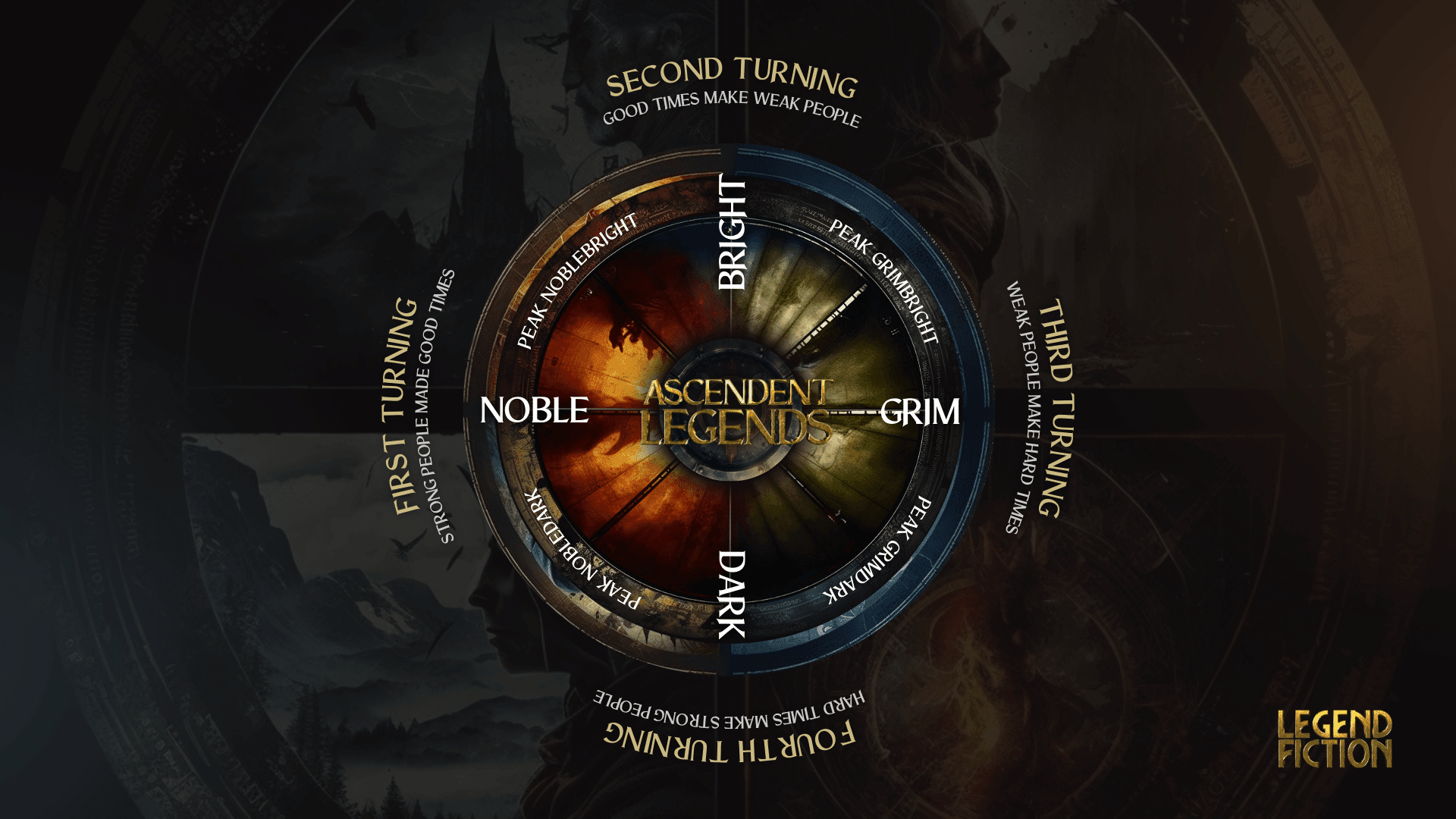

I was recently browsing the RealmMakers Facebook group, and saw a chart that utterly fixated me. It had extremely cool names like Grimbright and Nobledark in it. I needed to stop everything and know what these categories were.

The article ‘The Generational Cycles of Grimdark vs. Noblebright‘ is a good read, a fascinating overview of a turning cycle of stories that fascinate us in each generation. Take a moment to read through it.

I want to take their ideas a step further. But there’s an immediate and practical value to knowing this wheel. We all create fiction according to what’s popular in the moment. But by the time we’ve finished our draft and sent it to the publishers, they are inundated in similar stuff. “Sorry, doesn’t fit our needs at this time.” Is your story worthless? Of course not. It might be a timing issue.

Can we ‘hack’ timing? What if you could get a glimpse into how the human soul works, and how our culture is a turning wheel of expectation and failure? You could create content ‘ahead of time,’ and – I imagine – have a better chance at success.

To summarize their post, they refer to Strauss-Howe generational theory, available as a book called ‘The Fourth Turning.’ Two historians were charting the generational flow of ‘personas,’ like an archetype. Each generation responded to life in a common way, leading to predictable outcomes:

- Strong people make good times

- Good times make weak people

- Weak people made hard times

- Hard times make strong people

Each ‘turning’ of this imaginary generational wheel is a generation, about 25 years. Perhaps a full century goes through all parts.

This post outlines the four fascinating and dramatic themes that mark human living, following the medieval Wheel of Fortune, the yin-yang, and some generational theory.

The Wheel of Fortune and Yin Yang

I look at this, and several thoughts come to my mind. One is the medieval view of the Wheel of Fortune, a spinning cycle of good and bad luck – as long as the person is swinging round on the edges. Each quadrant on the wheel has a Regnant Virtue, and an Attendant Flaw. Only in the center is there a chance at stillness.

Bob Wiesman, the author of the post, says:

“Human experience leads a person up and down the Wheel of Fortune many times in the course of a lifetime. Each stage beckons man with its various temptations from pride to wrath to despair to ambition, and each stage compels man to resist the temptation with an opposing virtue from humility to meekness to fortitude to temperance.”

This can be a generational cycle. It can also be a cycle of phases of human living. We all go through it several times in our lives. We can see it in modern media, how people hunger for specific kinds of stories depending on what we experience as a culture.

As authors, we might write a novel set in a specific quadrant. But then the next novel might be in a different part. We may even have a single novel go through several quadrants.

This ‘Ascendent Legends’ graphic is a ludicrously dramatic take on the same genius of the yin-yang symbol, or the story of the Hebrews following Moses in the desert. The Hebrews did not distill their central ideas into neat pictograms or symbols. Their ideas stayed entrenched as stories, their symbols shown through parables.

That’s why the pillar of fire and the pillar of smoke is a direct match with the yin-yang symbol. For the east, this symbol reflects the constant turning of the wheel of fortune, of life. Nothing is ever all-perfect or all-evil under Heaven. Every good time has a flaw, and every dark moment has a point of light. The wise person learns to see this in a constant state of awareness. They learn to ride the line between the cycle, the hairline of detachment and stillness.

The Pillar of Cloud and the Pillar of Fire in Exodus 13:22 never stopped guiding the people. Both these pillars are the presence of the Wisdom of God, ahead of the people, leading them to the promised land. The pillar of cloud ‘blocks’ the realm of sunlight, casting a shadow, like the dark spot in the white yin. During the yang dark of the night, the pillar of fire is like sunlight.

So let’s get into more of the definitions.

The Noblebright and Grimdark definitions

These are four axis of generational growth. Every individual goes through a similar cycle in their lives, the same way we are all teens and adults together. Each phase of live can come with dreams or nightmares. If a culture is in very close sync, most people in a generation will be attuned to the same feelings.

Today, social media and a 24/7 news cycle keeps many of us seeing the same stories, news, and projections. This means that more than ever before, we may be in a generational lockstep.

- Bright: the Ascendance of Moral Good, or Power: Bright refers to what’s accepted by a culture as ‘good living’ and ‘right action,’ order and creative collaboration that makes for happy, human thriving, in the service of their gods, or the highest ideals.

- Dark: the Ascendance of Moral Evil: Dark refers to everything that creates chaos and is ultimately destructive to human living. It is isolationist and malevolent, in the service of ugly and cruel gods or our lowest parasitic urges.

- Noble: the Internal Ascent into Heaven: The heroes are personally convinced of the goodness and value of their culture and the need for heroic action, that their self sacrifice of position, freedom, life, or comfort for long term adventuring and endurance is the necessary and obvious choice. They hunger for a moral reward before material. These are the good heroes, the saints, the admirable, epic, godly, and godlike.

- Grim: The Internal Descent into Hell: these are the anti-heroes who strive to survive or succeed. They have no inner conviction about moral good, but expedient good. The gods, or transcendent ideals, have no real influence apart from wielding the masses. Often cynical, these are often disillusioned, violent, undisciplined, and joyless tricksters or rebels.

Bright and dark are always in a cycle in human living. These are the contexts, the exterior world. The moment a culture tells itself they are ‘the good guys’ is when they start sliding down the next side of the wheel, toward the dark. At the top, pride and rigidity take place of interior growth and a fluid openness to goodness.

But it is the breaking apart and experience of darkness that forces us to face our own weakness and evil. It’s the spot in the white tear that we papered over, that spot takes over like blood in milk. The contrasts must exist. Wise living understands that this is human reality: grace and sin side by side, abounding in every choice and moment.

We can take Bob Wiesner’s medieval wheel of fortune and map it’s regnant virtue and attendant flaw like this:

- Noblebright: Ruling with power, but struggling with pride

- Grimbright: Beginning loss of rule and ensuing frustration

- Grimdark: Loss of all power, and languishing in pain and sloth

- Nobledark: Beginning regain of rule, fueled by ambition and stained by manipulation

The world of our interior lives exists in reaction to this context: we react, resist, rebel, or renew life.

Noblebright: the throne on the heights

The world is bright, and the culture maintained by saints and heroes

Noblebright stories will have plenty of danger and darkness in them. The context is that there is an obvious goodness to culture, and an obvious goodness to its heroes. The stories end well, because the adventure is all about maintaining the centrality of goodness. Characters don’t have time or need to doubt. If they do, they end up recommitting to the best and brightest of human and divine wisdom.

These are the best of times, times that create peace and artistic flourishing, building and growth. These are the golden days we get nostalgic about. These are the times we all work to build. Noblebright is anchored in a very clear sense of moral good and evil, and from a spiritual standpoint, things are where they should be. The goal of the stories is to bring order out of chaos by following a clear map of meaning.

It might be easy to say that Noblebright is ideal human living, and we might be right. But the central mystery of our faith is the Grimdark Golgotha. Humans will always need to journey into the underworld and come back renewed. Ideal human living is about knowing how to navigate these adventures so that we grow.

Grimbright: descent into darkness

The world is bright, but a grim shadow reigns in the hearts of people.

The children of a Noblebright Ascendant world might grow up so safe from danger and consequences that they don’t take inner growth seriously. So they become cynical and manipulative. Their stories are about the blind breakdown of the Bright world, cycling into hell.

These are our cautionary tales. The world is falling into shadow because of weak leaders and evil rulers. The gods seem to have gone, only because people have turned away from them. Good living and holiness are not the cultural expectation. Cynicism reigns, and characters butt up against the brunt of survival. Sometimes we need stories that imagine life without goodness to reappreciate the good we have.

Every hero and human must go through a personal hell to test their convictions. Hell is always intimately personal. These heroes are not saints. Not yet. Maybe not ever. These stories will probably shock us and end in failure and sadness, but that’s because their lesson is critical. We can’t become too attached to the outcomes and success of our efforts. This genre reminds us that our lives are a tapestry that begun before birth and continue after us. We don’t have the control we want, and sometimes our lives feel like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

These stories are about a breakdown into chaos. The character might be marked by a dark and traumatized upbringing, and they are a long way from wholeness. They see an immediate need to hold back evil, to create a culture and community that is freeing and good. But goodness stays at the level of human living, not holiness. So they often play all sides, and are willing to fight and die and live for the goodness they understand.

Grimdark: How far we fall

The world is dark, and darkness reigns in the hearts of men.

Grimdark stories remind us of this body of living death that we endure. Death is a critical and constant part of living, whether it’s people, things, institutions, agreements or egos dying. We all must endure this.

These stories remind me of the Holocaust, horror stories, or antiheroes; there are no winners, it’s too late for change. The only hope is to survive to make it to tomorrow. There’s so much trauma that we can’t think about moral wellbeing. These are often the horror tales where we look deep into our mirrors and pensieves to remember how far we can fall.

These stories are meant to grab us by the throat and shake us to wake us up as viewers. They play on our rancid fascination with sin and malevolence and chaos, and deliberately challenge us to stare deep and long at the impact of a living hell here and now. We stare at the tragic glory of a human being frozen in their life like a burning ember, meant to flame like a star, and instead constipated by ego and stabbed by evil.

If Grimdark breeds a renewed love and taste for hearty moral living, where the only way through is to change who you are – and want the change – then we start making the culture bright again. This nobility of sacrifice is the turning back to the light, the incandescence of the spirit as the life of the gods flares up again.

Nobledark: the dawn of morning

The world is dark, but the heroes are fueled by a noble sacrifice to seek a new world.

This is a phase in all our lives where we might feel we’re fighting a long defeat, never able to reach the bright goal we hope for. We have internalized the good and Gods the culture, but the works around us have gone to hell. There are only bittersweet endings, because good is not fully ascendant yet. We are conflicted at the compromises we have to make, because of how far we have yet to go.

Evil may seem to triumph, and the heroes die or have their efforts come to nothing. With such stories, the viewer is invited to see beyond the ending. It is about candles in the dark, where bold witness catalyzes a new world, lighting a new way without support. From the point of view of a single human life, the effort might be a glorious waste or a hopeful failure. The stories are about being an angel in hell, rather than being a devil.

I think of war heroes like Cristeros in the Mexican Revolution, or the Japanese rank and file during WW2 felt this way. St Maximilan Kolbe seems to have died as a waste, to the Germans. From the long view of Heaven, he burns bright like a saint. Jesus Christ is this sort, Joan of Arc, Fr. Miguel Pro and the early Christian martyrs. Ragnar Lothbrok from ‘Vikings,’ or ‘Gladiator,’ or ‘Last Samurai,’ or ‘Game of Thrones.’

The good outcome may or may not be seen. The happy ending is a good and true life in spite of the darkness.

The wheel turns

These are a series of spiritual reflections. Each one is not ultimate reality. They are imaginal views of what’s happening around us. Imaginal doesn’t mean imaginary. It means mythical, archetypal – from the point of view of life beyond human limits, the level of reality where time makes contact with eternity. Human minds touch that liminal realm constantly, but don’t know it.

Fantasy stories are not always about a mystical Ragnarok that cleanses the world of all evil. Children’s stories are often that way, because we need to ground them in this deep hope.

But for adults, after every ‘The End’, there is always an unwritten chapter 1 of the same heroes having a bad day. There is always the Return of the Shadow.

Faith-inspired fiction is much more than a battling dyad of light and shadow. These the simple tones of children’s stories. The adult understands that God brings good out of evil, and humans turn good into shadow, in a constant cycle.

Some practical takeaways

I’ve seen this Fourth Turning cycle used as a way to condemn our modern culture, that we’re in bad times created by weak men. People who don’t know enough history, or movies, will act as humans always do; this is the preface to the end of times.

But if Grimdark is a thriving of sin, then it is also and always a seedbed of new graces. Romans 5:20: Where sin abounds, grace abounds more. We can begin to see the turning of the wheel in our time. As chaotic as our culture is, some of us are driven to work and fight for a better world.

And here’s a key thought. The wheel may turn, but it can also be interrupted or influenced. A generation in a different culture is on a diferent part of the cycle, depending on what’s going on in their country or culture. Our continent is not in lockstep, and the wheel may be in different quadrants depending on state, place, or community.

This is a key reason why we can’t despair over an imagined ‘culture war.’ As soon as you pay attention to it, the idea dissolves and has no definition. Culture where? Among who? Our country is a tapestry of subcultures. Our world is a landscape of even more. Some of them overlap. This re-fracturing back into intentional cultures built around meaning, purpose, and community, will replace and outgrow the sleepy lockstep of past mindsets.

I’m not convinced that a country in a grimdark state nurses itself with grimdark stories. I think a Grimdark people will look forward to the new Nobledark, and pull the wheel to change. In a time of Noblebright, it makes sense to remind ourselves of Grimdark stories, so that we are better equipped to get off the rim of the wheel, and find intentional stillness – known as holiness and humility.

The theory doesn’t state that each fantasy form’s antithesis dies completely when that form is ascendant: only that it reaches a nadir of decline in its resonance with the culture. But without sufficient contrast, the ascendant form cannot stand out. Thus, there still has to be some noblebright Paolini to provide sufficient contrast with the grimdark of Abercrombie and Martin, some low fantasy slice-of-life Legends and Lattes grimbright to make the epic nobledark high fantasy of Sanderson stand out stronger.

I don’t class Martin as Grimdark at all. ‘Game of Thrones’ is very definitely Nobledark. But if you stop early in the story, without understanding the ending, you’ll definitely feel the loss of hope and purpose in the characters.

So with all this in mind, we can roughly assess where we think the culture is now, and what people are hungry for now. This might help you see more clearly what kind of story you’re creating, and if its the perfect time to try and get it published.

More importantly, I hope that this wheel is more then a fictional gimmick. It can also be a spiritual tool for you and me to be more patient with ourselves, to perhaps glimpse where we might be on our own personal dances with Holy Wisdom and the mystery of God. To cultivate a constant openness and hope to grace, no matter the shadow. And a patience with the presence of weakness and flaw, no matter how good things seem to be.

I need your help with ideas for books and movies that fit in each quadrant. Can you help me in the comments with any obvious titles?

What is your story’s quadrant? Comment below!

Cyberpunk 2077 immediately springs to mind for Grimdark. Technically a video game, but the storyline and plot elements of it are better written than just about every other Grimdark story I’ve read. There is darkness, and every evil under the sun rears its ugly head. It’s very much a commentary on how hedonistic humans have become, and how the evils we so comfortably rub shoulders with could overtake our lives in just another 54 years.

The Inkheart Trilogy goes through a shift from Grimbright to Nobledark, starting out in a relatively okay world and swiftly becoming almost apocalyptic in how fallen its fantasy world has become. But there is redemption, and plenty of characters who are willing to fight for good.

Katy Campbell’s “Love, Treachery, and Other Terrors” seems like Noblebright to me: a pretty decent world that always has a taste of ignoble things lurking beneath the surface, temptations that characters need to face, and villains that need to be stood up to.

Very impressed at your suggestions. Thanks Max!

I think Cyberpunk 2077 can go in ways not grimdark, though. At the core of that story is the redemption of Johnny Silverhand. You can play it like a right, well, but you can play it like a person trying his or her best in an ugly world; there are compassionate responses to many quests, though many times the player is too late to make a difference and tragedy has already occurred (the Bethesda storytelling method). I don’t think that world is hopeless- you see people who choose something more than the choking materialism over and over, building lives that are marked by a true joy even in the midst of a world that sows so much sorrow. You see the opposite plenty, which is all the more tragic because that’s not the only path. It’s not a world that can be saved, but people can choose to be. In video games, that makes it a very unconventional narrative.

Thanks for chiming in, Kathryn! Great points.